Dogs love to sniff, right? But how often is the average pet dog actually using its nose in everyday life, and what does sniffing – or not – tell us about a dog’s state of mind?

Dogs love to sniff, right? But how often is the average pet dog actually using its nose in everyday life, and what does sniffing – or not – tell us about a dog’s state of mind?

Super sniffers, or do the eyes have it?

Incredible. Amazing. Almost magical. If we used any of these terms to describe a dog’s sense of smell, few would argue. After all, there are reams of research showing the many ways in which dogs are used for their superhero olfactory capabilities: to sniff out cancer, to detect dangerous explosives, to locate bedbugs and other pests, to find lost humans in the woods, and heck, even to track marine wildlife while on a boat in the ocean (!).

But did you know that, unless they are specifically trained in scent work, dogs will often use sight – not smell – in everyday decision making? That’s right: whether it’s differentiating a large quantity of food from a small one(1), or accurately choosing between their owner and a stranger(2), the average dog often chooses sight more frequently, and uses it more effectively, than smell. In fact, when asked to rely on only smell in such studies, dogs generally perform at only chance (~50-50) levels.

Hold it right there, you say! How can this be?! Dogs’ noses are so incredible, amazing, almost magical. How could they NOT make use of this superpower at every opportunity? Think of it this way: using sight is like scrolling through the headlines on your Facebook newsfeed. Using smell is like clicking through and reading an article.

Sniffing is exploratory; when dogs sniff they are actively gathering and analyzing information about the world around them. Just as we don’t have the time, mental resources, or motivation to read every single article we come across, dogs aren’t going to use their fantastic sense of smell to analyze every single thing in their environment; and so they use sight for quick and easy (though incomplete) information gathering and decision-making.

Smell Check: Sniffing Habits and Emotional States

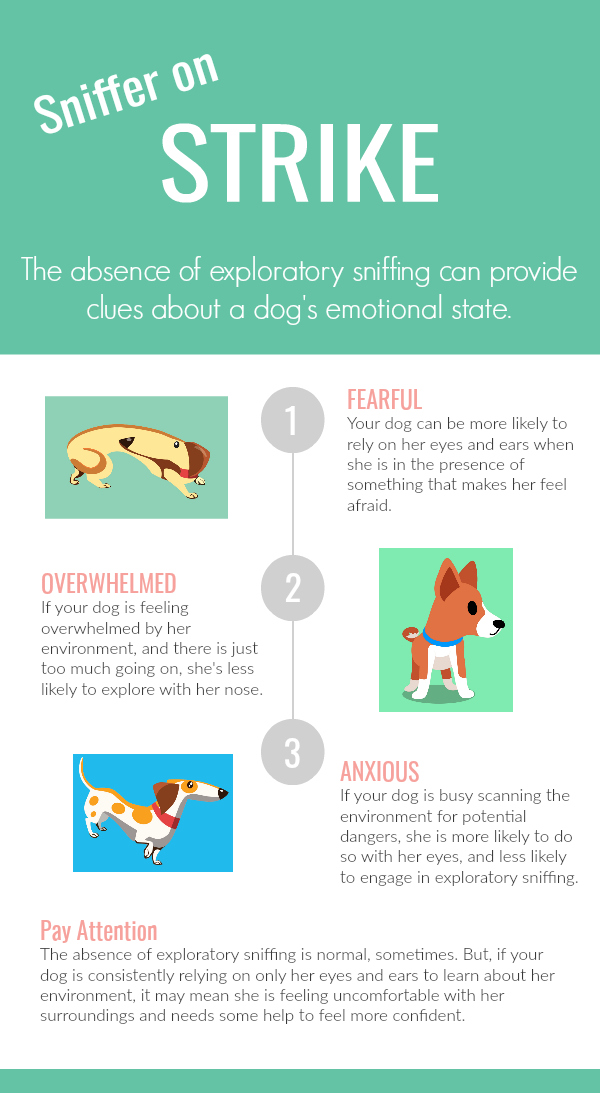

Dogs sniff sometimes, but not other times, and that’s a normal part of selectively filtering information. But taking a closer look at your dog’s sniffing habits can reveal important information about how they’re feeling in different situations.

Dogs sniff sometimes, but not other times, and that’s a normal part of selectively filtering information. But taking a closer look at your dog’s sniffing habits can reveal important information about how they’re feeling in different situations.

Let’s go back to the Facebook analogy: we are far more likely to click on and read an article that is interesting or personally relevant to us, and less likely to do so if it’s something we don’t really care about. That’s normal. But, we are also less likely to read the article (to engage in information-gathering) if we are stressed, anxious, tired, overwhelmed, in a hurry, or distracted by something else in the environment.

If you notice an absence of exploratory sniffing – either air scenting, with their head up and sniffing the air, or ground sniffing, with head down and snuffling along the ground – from your dog in certain situations or environments, it could mean they are also feeling stressed, anxious, or overwhelmed. This will happen occasionally, and it’s normal. But if you notice a pattern of your dog observing her environment using only sight and sound, and rarely smell, it’s likely a sign that she needs some help to feel more confident, relaxed, and comfortable out in the world.

Teach Your Dog to Read the Articles

As humans, we often need to be taught and encouraged to ‘read the articles’ – to seek additional information and to think critically about that information – especially when we encounter something new and unfamiliar. It’s easy to make a snap judgment (angry Facebook emoji!) with limited information, especially about something that is unfamiliar to us or that makes us a bit uncomfortable. Taking the time to gather additional information gives us confidence and helps us feel more secure about these new situations and topics.

The same is true for dogs! If you have a dog who is anxious or uncomfortable in certain situations, they can also be taught and encouraged to slow down and gather additional information through their nose, to help them feel more confident. An easy place to start is by introducing your dog to some beginner scent games at home, then slowly starting to play those games in more distracting situations. You can also teach your dog a special sniffing cue, such as “Check it Out” to encourage them to use their powerful nose to gather a wealth of valuable information about the world around them.

Try it! Introduce a “Check it Out” cue

- Start in a safe, low-distracting environment where your dog is comfortable and relaxed.

- Hide a treat under a small piece of paper, then point and cue your dog to “Check it out!” Praise when they get the treat.

- After a few repetitions like this, introduce additional pieces of paper, but place a treat under only one of the pieces. Again, cue them to “Check it out!”

- At first, your dog can watch the whole process of you placing a treat under one of the pieces of paper, but as soon as they’re enthusiastically moving in to retrieve the treat, you should prevent them from seeing where the treat is placed (so they switch to using smell, instead of sight, to locate the treat).

- After practicing over several days, in short sessions of just 1-2 minutes each, try giving the cue, “Check it out” and pointing at something in your house (a backpack, a plant, etc.). If your dog moves to the object and sniffs for just a second, praise and toss a treat on the ground next to the item.

- Repeat the game, slowly branching out to more objects and environments over several weeks, and waiting longer before praising and rewarding with a treat after your dog sniffs.

Want to learn more about a dog’s incredible sense of smell? Check out this truly fantastic video by Alexandra Horowitz, “How do dogs ‘see’ with their noses?”:

Happy Training!

Sarah Fraser, CDBC, CPDT-KA, KPA-CTP

Co-Founder

- Horowitz, A., Hecht, J., & Dedrick, A. (2013). Smelling more or less: Investigating the olfactory

experience of the domestic dog. Learning And Motivation, 44(4), 207-217. doi:10.1016/j.lmot.2013.02.002

- Polgár, Z., Miklósi, Á., & Gácsi, M. (2015). Strategies used by pet dogs for solving olfaction-

based problems at various distances. Plos ONE, 10(7)